In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural

Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her

name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening

web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the

foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the

operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to

do the procedure, but told the child's parents and advocates that if anyone was

going to attempt this, they'd need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th street in Manhattan, is the

Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively

treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. "I'm

the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating]

vascular anomalies," Waner tells Medscape.

Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at

the institute's offices in Lenox Hill — including his wife Teresa O, MD, a

facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. "People

often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?" Waner

says. "We work extremely well together. We complement each other."

O and Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in

January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the

child's advocate and reviewing images, they agreed to do the surgery, fully

aware that they were one of only a handful of surgical teams in the world who

could help her.

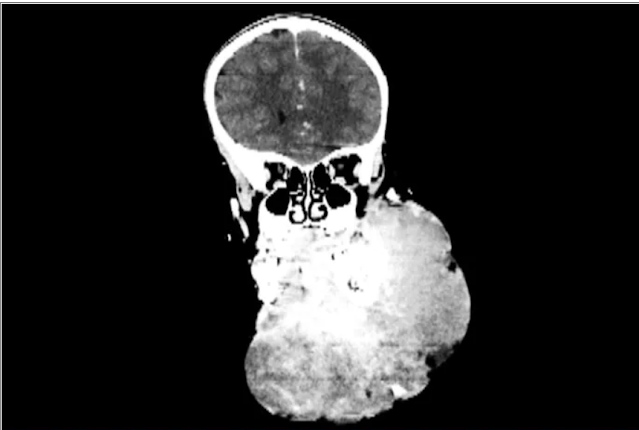

An image of a scan of the patient before

surgery.

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Waner

says, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have

an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300

mL of blood, "that's 20 or 30% of their blood volume," Waner said. So

the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many

blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived

in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was

organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children

Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel

stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and

post-surgery care. And Drs. O and Waner did the planning, consult visits, and

procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of

several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove

the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the

patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure,

done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood

vessels which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit

bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient

underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn't have the intended

effect, Waner said, "because the lesion was just so massive."

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time.

But this isn't the sort of surgery you'd find in a textbook. Because it's such

a unique field, Waner and O have developed many of their own techniques along

the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only

"several orders of magnitudes greater," Waner said. "On a scale

of 1 to 10 she was a 12."

Negalem, 5, before her surgery.

The morning of the surgery, "I was very

apprehensive," Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl's father repeatedly

kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that

this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were

challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth,

deformed by the tumor, didn't allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical

tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and

tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures

tangled in the anomaly. "The jugular vein was right there. The carotid

artery was right there," Waner said. It was extremely difficult to

delineate and preserve them, he said.

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the

growth had adhered to the jaw bone. "There were vessels traversing into

the bone which were hard to control," O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they'd be able to remove

it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and

reanimation.

The child's jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal

size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial

symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child's facial nerve

control. With it gone, O began the work of finding all the facial nerve

branches and assembling them to reanimate the child's face.

Before medicine, O trained as an architect, which, according

to Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness — a valuable skill

in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Waner, she

immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship

training with Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in

facial nerve reanimation. The proof of O's expertise is Negalem's new,

beautiful smile, Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of

surgeries for the two doctors. When O finally walked into the waiting room to

inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father's mouth

were, "Is my daughter alive?"

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal

life. Waner's mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this

case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn't been removed, the child was

only expected to live 4 to 6 more years, Waner said. Without the surgery, she

could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a

fatal bleed..

O and Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work,

but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary,

multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial

nerves — they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with

these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition

to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post-op, "it was a

lot of teamwork," O said, "a lot of international teams coming

together."

Though extremely difficult, "in the end the result was

exactly what we wanted," Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And

as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. O said,

"I'm honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and

work with Milton. I'm so happy to do what I do every day."

"That's why we really took our time. We just went very

slowly and deliberately," O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that

their only option was to move painstakingly slow — otherwise a small nick could

be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was

"excruciatingly difficult," Waner said. And early on in the

dissection he wasn't quite sure they'd make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn't

done much to prevent bleeding. "At one point every millimeter or two that

we advanced we got into some bleeding," Waner said. "Brisk

bleeding."

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of

surgeries for the two doctors. When O finally walked into the waiting room to

inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father's mouth

were, "Is my daughter alive?"

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal

life. Waner's mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this

case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn't been removed, the child was

only expected to live 4 to 6 more years, Waner said. Without the surgery, she

could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a

fatal bleed.

O and Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work,

but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary,

multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial

nerves — they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with

these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition

to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post-op, "it was a

lot of teamwork," O said, "a lot of international teams coming

together."

Though extremely difficult, "in the end the result was

exactly what we wanted," Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And

as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. O said,

"I'm honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and

work with Milton. I'm so happy to do what I do every day."

Donavyn Coffey is a freelance journalist who covers health

and the environment from her home in the Bluegrass. Her work has appeared in

Popular Science, Insider, and SELF.

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/954312